Pandemic Academic: A Look Back On The Pandemic’s Lingering Effects On Education

Well, COVID happened. It was a tragic, terrible, and tumultuous time for the world. Among other things, it gave birth to what used to be one of my favorite excuses ever: just blame COVID. We seem to be doing that a lot lately. But is that really a good habit? I think we all have to stop doing this. Historically, when we start blaming other things for our own problems, it just means we are unwilling to admit they are our fault. I’d argue that our handling of the COVID-19 pandemic has given us these problems. There are many things we have blamed on the pandemic, and the one I will talk about today is the poor academic progression of U.S. students.

How we, as a country, did schooling during the start of the pandemic (March 2020) and how we continued to deal with it in the next few years show serious negative impacts. According to the Brookings Institution, math scores from the fall of 2021, from third grade to the end of middle school, were 20% lower than those from the fall of 2019. This significant drop-off is wildly concerning.

The question is, why did this happen? It might seem obvious, but if it was that obvious, we would have fixed it by now, right? So what’s so obvious? Learning online and at home ruined the academic progress of our nation’s students. With no supervision and unlimited internet access, and with every answer a Google search away, most students went the easy way out. They are now showing the fruits of their effort or lack thereof. But can we really blame them? The virus shut us down in an unprecedented way. We were stuck in our homes with no real human interaction save that of our families, and we still had to do schoolwork. So if you can’t blame the students, do you blame the teachers? No. How were they supposed to adapt to online schooling on a dime and ensure their students stayed caught up? There really was no good solution.

So who is to blame? It must be a combination of the two. Students could have applied themselves and risen to the challenge of online schooling, and teachers could have worked harder to make sure no one fell behind. But really, that wasn’t going to happen. Students were always going to fall behind, and it was too much to ask of the teachers to convert all of their lessons to online and not lose their students’ progress.

Now it is important to ask the question why it matters that students are falling behind. Is it really that big of a deal? Couldn’t we just curve the grades to maintain consistency from year to year? Suppose you are against that type of curve—which I am. In that case, you must think that the school system evaluates our students’ competency and computation to some extent. I know, that’s quite the bold claim. Despite some naysayers claiming the education system is in trouble, the tests in schools evaluate knowledge our society needs.* Suppose we just curve the exams to make it look like the education system still produces the same quality of students. In that case, our society will eventually become more and more incompetent.

But what’s happening is U.S. students are performing poorly, and we are not curving to maintain consistency, so the results of the pandemic are obvious to all. An article from McKinsey states that, at the end of the 2020-2021 school year, students were, on average, five months behind in math skills and four months behind in reading. I am sure that this number is probably underselling the problem. There were lots of students who were more than five months behind in those subjects.

And now, these same students are required to take state and national exams. Exams that have yet to be changed to meet the material missed by the students taking the actual exams. Now, one could argue that the students should be ready for these tests because they were taught the material. Again, we bring up the question of whose fault it is they are behind. No one answers these questions, and gifted students with the means to do so go off and score well, leaving those who fell behind. So is the answer to curve these exams? No. The exams need to be adjusted, and we need more teachers, and our current teachers need more help. The education profession is being put under immense strain. I also propose that those students who score well begin helping their fellow students to help relieve some of the strain from the teachers.

And now, these same students are required to take state and national exams. Exams that have yet to be changed to meet the material missed by the students taking the actual exams. Now, one could argue that the students should be ready for these tests because they were taught the material. Again, we bring up the question of whose fault it is they are behind. No one answers these questions, and gifted students with the means to do so go off and score well, leaving those who fell behind. So is the answer to curve these exams? No. The exams need to be adjusted, and we need more teachers, and our current teachers need more help. The education profession is being put under immense strain. I also propose that those students who score well begin helping their fellow students to help relieve some of the strain from the teachers.

But how do we solve this problem? We need more teachers. Teachers recognize the need, and they recognize the problems, but they are stressed and overworked. Seeing our teachers this way is not a good advertisement for us to pursue teaching. At the end of the day, though, some of us need to follow that path. I think the place to start is starting to give a little more respect to the teaching profession and give our students a break; they have been through a lot lately.

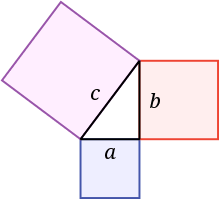

* I know, I know. “Charles, when will we use the Pythagorean theorem in real life? When will we have to write an essay for our job? [Ed. Note—it’s called a cover letter.] Really, I meant more the lessons of hard work, self-discipline, and organization required to complete school.