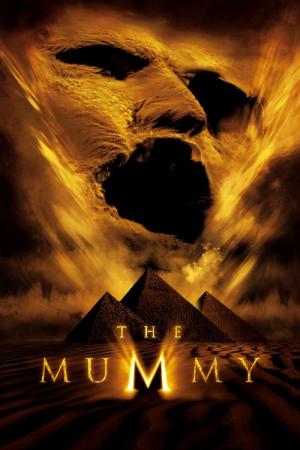

The Mummy (1999): A Retrospective

Examining a flawed masterpiece

As I’m sure all my loyal readers have noticed, I haven’t written an article for the Shield in quite a while. Unfortunately, schoolwork and hobbies have left me with limited free time, meaning I’ve had very little opportunity for movie-watching. However, in my busy schedule, I’ve still (for some reason) managed to make time for one film: 1999’s The Mummy. Unlike many young people, I didn’t watch The Mummy until my teenage years, so I don’t really have any nostalgic childhood memories of the film. With that being said, I still think this movie is worth talking about for multiple reasons, good and bad. I’m going to throw aside any semblance of formality and structure for this article, for two reasons:

- While I enjoy this movie very much, it happens to not be very “good” in the traditional sense. The plot makes minimal sense, the script is often hokey, and the CGI has held up about as well as you’d expect from a 1999 film. Because of this, I feel like any sort of logical review format wouldn’t do The Mummy justice. Because even though the movie generally doesn’t pass muster on a “competent filmmaking” level, it more than makes up for this on the (equally as important) “fun” level.

- As of this writing, there are about 12 hours until the submission deadline for this issue, and loose collection of thoughts sounds much more appetizing to my sleep-deprived brain than professional work of film criticism.

Alright, so I’ve given you a brief idea of what The Mummy gets wrong. But before I go into what it does right, here’s a very brief plot summary:

Rick O’Connell (played by Brendan Fraser) is an American adventurer who teams up with a British brother-and-sister team of archaeologists to uncover the secrets of the lost ancient Egyptian city of Hamunaptra. On this quest, they inadvertently awaken the corpse of the evil Egyptian priest Imhotep, who goes on a murderous rampage across Egypt until (spoiler alert!), he is defeated by O’Connell and company.

. . .which is about all you have to know. Of course, there are intricacies to the story, but it certainly isn’t the plot that makes this movie worth watching. Instead, it’s The Mummy‘s relentless pacing that provides it with its immense entertainment value. I can’t think of a single wasted moment in this film; it’s stuffed to the gills with sweeping wide shots, bombastic action, and enough quips to make a Marvel movie blush. So even when the plot is flimsy (or just doesn’t make sense at all), you don’t really have time to care. The movie is singularly committed to providing the maximum amount of fun for its viewers—a goal in which it wholly succeeds. Another reason for The Mummy‘s success are some fantastically over-the-top performances, led masterfully by Brendan Fraser. As goofed-on as he is, Fraser was truly the perfect actor to lead this film. He provides a real sense of presence in action scenes (at least partially due to the fact that he’s 6’3″) and he’s an extremely physically expressive performer—both essential traits for such an off-the-rails movie. It’s a real shame how much of a decline Fraser saw in his star power, although some exciting new roles may just prove to spark a career renaissance. (Here’s a great article going more in-depth about Fraser and what he’s been up to.) But despite my appreciation of The Mummy as a piece of entertainment, the film’s cultural attitudes haven’t held up as well as its action:

Orientalism is “the representation of Asia, especially the Middle East, in a stereotyped way that is regarded as embodying a colonialist attitude.” After reading this definition, those who have seen the movie probably have an idea of where I’m heading with this. See, despite taking place in Egypt, The Mummy offers very little respect for that country and its people. Almost all of the film’s leads are white, and the characters who are Middle Eastern/North African are almost exclusively working for the bad guys (one of the few “good” Egyptians is almost exclusively referred to by the main characters as “our smelly friend”). These aspects, combined of the fact that there are zero Egyptian actors with speaking roles, speak to a mindset that doesn’t really value non-Western creative input. Although I know very little about ancient Egyptian mythology, this film’s version of it seems to be absolute gobbledygook, and Egypt itself feels more similar to Middle-Earth than the Middle East.

Now, I don’t bring these things up in an attempt to “cancel” a movie that has already grossed hundreds of millions of dollars (though some Egyptian people might justifiably disagree with me). Instead, I hope to simply contribute to the growing discussion surrounding diversity in film. While it’s easy to think of racist movies as a thing of the distant past (think Gone With the Wind), the uncomfortable reality is that The Mummy wasn’t made all that long ago. And while I do genuinely believe that since 1999 Hollywood has gotten better at telling stories that are authentic to global perspectives, it still has a long way to go. For example, the latest reboot of the Mummy franchise (this one made in the supposedly more culturally enlightened year of 2017) still features both a leading man and director who share no connection to Egypt or the surrounding region. All art has a responsibility to avoid exploiting other cultures for entertainment; a responsibility that too many films seem to disregard. So for as thrilling as it is (though still not quite as much as the Universal Studios ride), The Mummy whiffs on a golden opportunity to tell a story from outside the bounds of a Eurocentric worldview.