This was supposed to be our Valentine’s Day issue—a memo apparently not a single one of my writers got—but I think I can best illustrate where I’m going with a different story.

When I was a junior, my high school had something called Noche de Bohemia. For one night, one of our assembly rooms got lit up in subtle red, we put black curtains down and some tables out, invited families and friends, and for three hours, we entertained them with various performances, mostly musical in nature.

Our librarian (as Puerto Rican as me, despite his name being the surprisingly-Anglo Ralph Manon, who recently passed) was supposed to emcee the night, but on the day of, he was so grievously sick that they had to call in a pinch-host to direct the proceedings.

You’ve probably guessed where this is going: they turned to me, because when you need someone to stand up, look serious and say something meaningless in between more talented performers, I am now and have always been your huckleberry.

Being the MC of this special night, though, also required reading a poem. It’s called “El brindis del bohemio” (“The Bohemian’s Toast”) and—to put it bluntly—it is not short. (Clocks in at 927 words, for those wondering.) By this, I do not mean that it is bad. Dramatic? Yes. Overwrought? Perhaps. Maudlin? Undeniably. Yet it remains a sterling example of what a poet can do when they are committed to displaying a sentiment in its full glory.

The good news was that I did not have to read all of it, nor was I expected to memorize it. The bad news is that standing at a podium and reading a poem out loud, with no blocking, is a very good way to put a crowd to sleep, and I had all of a school day to come up with a performance, so I did my best.

When I was tapped for that same role senior year, this time knowing I would have to read the poem, I insisted on memorizing it, but cutting it down to the essentials. Specifically, the last toast, the one with the most airtime and the least pretense, is from the character Arturo to his mother, whom he has left behind to live his Bohemian lifestyle, and whom he now dearly and painfully misses.

Again, some of you have probably guessed where this is going, but: my mother, who was about to lose her son to the wintry enchantments of Rochester, New York, was sitting in the audience, and every wonderful thing Arturo says about his absent mother, I at least got to say to mine.

Guillermo Aguirre y Fierro (with a name that euphonious, you can’t not become a poet) was born in 1887, the last year of the original New York Metropolitan Baseball Club. He died in 1949, when my father was two. Yet, in 2007, when he had lain under the earth for nearly sixty years, it was his words that helped me get across to my mother that I knew full well I was unlikely to ever come back to live in Puerto Rico—and that I would miss her every day.

I know I’m staking out an unpopular position here, because we live in a world that insists everything come pre-ground into complete accessibility with a profit motive attached, and poetry is entirely about the complexities and subtleties of the human soul. There’s a reason certain people really want you to think it’s silly stuff, and most of the time, it’s because they’re afraid of either letting you connect to other souls through the beautiful art of the verse, or they’re afraid of letting themselves do so.

Here, if I wanted to turn this into a confessional of my own relationship to poetry, I could add that every time I have lost a family member, it is Catullus 101 (“And forevermore, brother, hail and farewell”) that comes unbidden to my mind, or that as some of my students know, I got very lucky that some verses of Horace (“thrice blessed and even more / those who are held by unbroken bonds / nor, dissolved in evil quarrels, will their love unbind before their last day”) I memorized because I was getting married in a few weeks turned out to be on my master’s comp exams, or that I can still rattle off Robert Frost’s “Fire and Ice” decades after I first learned it on a lark.

I could tell you that, like pretty much every other high school student, I hated learning about sonnets—poetry’s about what comes from the heart, man, you can’t force that into a meter!—and then, when I finally had time to write some years later, found myself so deeply enjoying the creativity they forced on me that I wrote one about the first time I had pho.

I could tell you that the reason I have always loved the Aeneid more than the Iliad or the Odyssey, which is probably also the reason I chose to specialize in Latin, and therefore the reason I’m here writing this instead of trying to find a job teaching Greek somewhere, is because the first line in which the hero’s name is mentioned (extemplo Aeneae solvuntur frigore membra) portrays him as cold, weakened, and about to cry, and it mystified me that the Romans would have nonetheless held that up as their national epic.

I could tell you that I have always loved reading the poetry of other countries and other languages, in translation or not, because nothing acquaints you more quickly with the rhythms and images and the unique music of a language than when it is used to render a poet’s emotions at their least hidden.

I could tell you that, from personal experience, there are very few things people like seeing when they open a Valentine’s Day card than a love poem custom-written for them.

I could tell you that, before I made a lot of changes in my life, the most connected I ever felt to my emotions was when I wrote poems like the Muses and I had been childhood friends.

I could tell you that every year, I still try to memorize this poem, and this one, and that if I ever write anything half as good as a Bécquer poem, I will instantly become a being of pure light.

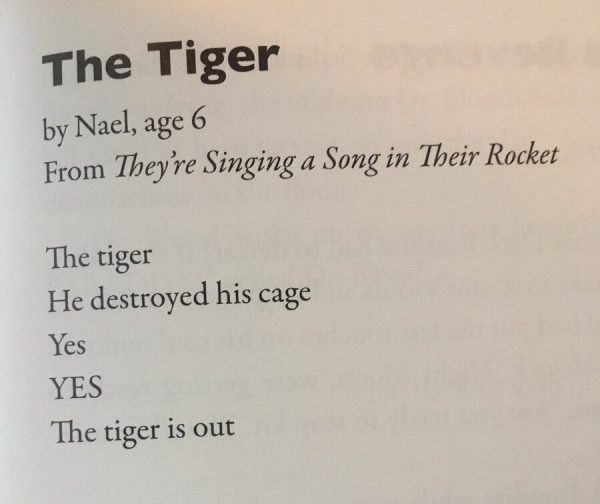

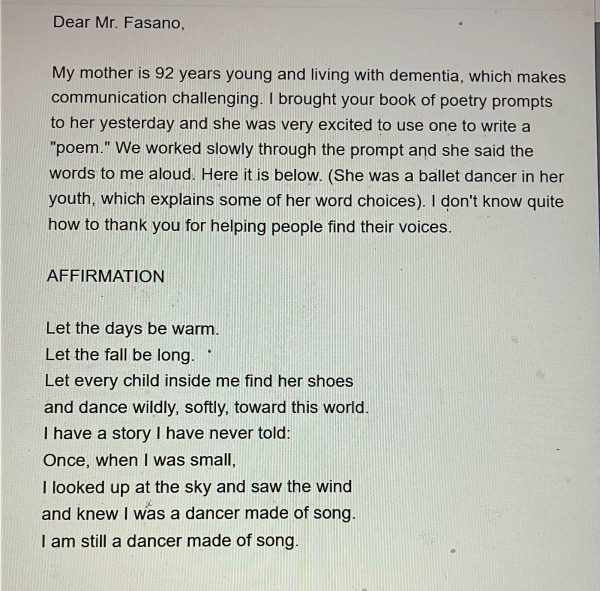

But the truth is that anything I could tell you pales in comparison to this completely coincidental find, which I came across shortly after I boldly said I’d write this article for our next issue of the Shield, and which immediately made me remember that the Holy Spirit exists and wants me to be happy, at least sometimes.

Chances are very good neither you nor I have ever met this woman. Chances are very good that neither you, nor I, will ever meet this woman. Yet, thanks to nine simple lines of simple words, delivered through one of humanity’s oldest and still swiftest art forms, if only for however long it took us to read that, in the very marrow of our bones, we know who she is.