Hello one and all. Welcome to another unhinged rambling about an obscure history topic loosely defined as an “article” that no one asked for, but I will deliver anyways. This is a follow up to the last article on Kokoda, so if you wish to know about the context go read that first. Anyway, let’s not waste any more time and jump right into it.

As the battle continued, the Japanese 144th continued its ferocious advance while the Australian 39th was scrambling for new defenses. After the 39th’s hit-and-run ambush (and a few more for good measure) the real battle was soon to begin.

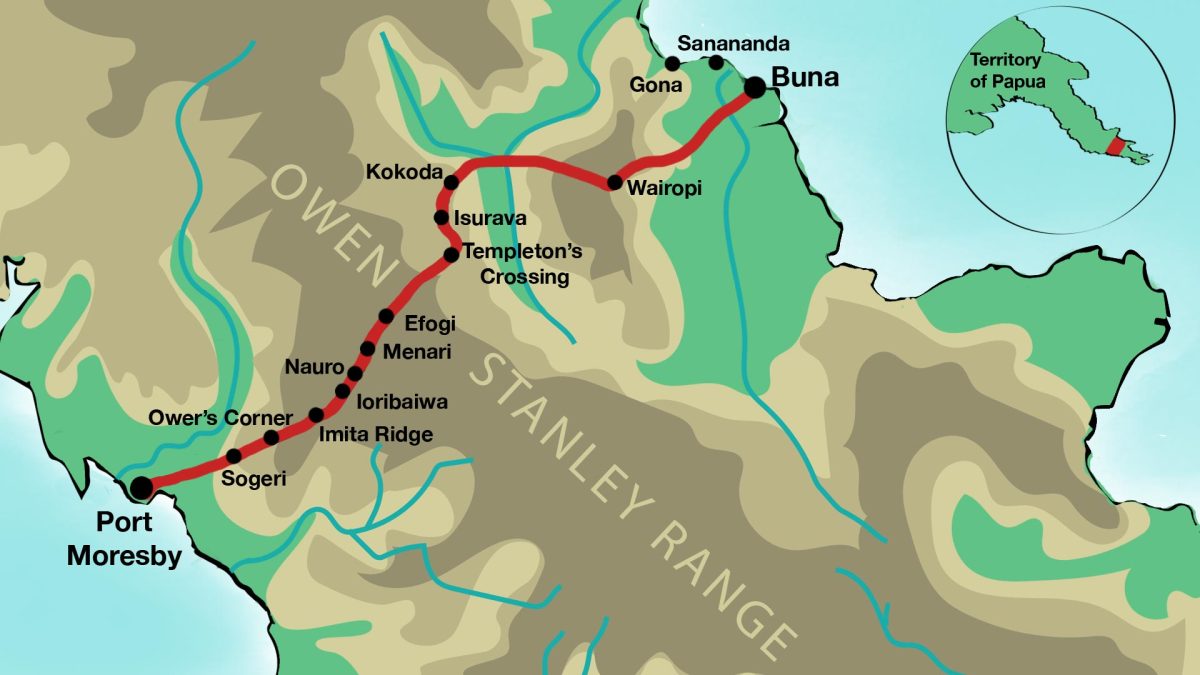

The 39th had retreated far enough; they were at the edge of Kokoda village, digging in to defend. The village was a fairly defensible position, as good as any in this area as the jungle was thick and could very well shroud entire columns from the eyes of the defenders. The area was protected by a small creek and slight elevation that provided good cover but invited the question: why defend Kokoda in the first place? It had what no other area did: an airfield.

This airfield was the only way, other than a week-or-more-long walk over the jungle-filled mountains, to get supply or reinforcements to the front, and was one of the only areas flat enough to even build one, which made the town extremely strategically valuable. The Japanese needed to cut this line of supply, as it was probably the most important structure on the track; by this point, they knew they could no longer simply march into the village, and prepared for full battle.

When the battle commenced on the 28th of July of 1942, the Australian side fielded around 140 men from the ANGAU, PIB, and D Company of the 39th. Against this, the Japanese deployed about 200 crack soldiers of the 144th.

The engagement started with a sudden attack; machine guns laid down a base of fire while mortars set up and launched shell after shell at the defenders, infantry moving up to the creek under this cover. During this, the Australians returned fire with rifles and their limited machine guns. While this barrage was going on, the Australian commander, Colonel Owen, ran through, rallying his men and returning fire while keeping them supplied with ammunition and good morale. Owen had been a father to his men, keeping them alive on their walk here, parceling out his own food, and carrying their packs and rifles throughout the brutal trip. He was the real driving force and inspiration for the men to keep holding on, despite the constant harassment of the Japanese and threats of the jungle.

The Japanese kept pushing, getting closer and closer to the defenders and reaching the small ledge at the creek. It was looking grim. They were close, and the Aussies were under big threat of being overrun when they came up with a plan: rolling grenades down the ledge and bank onto the Japanese, which did repel the attackers, although more kept coming. After the grenade volley, and even a bit before it, the Japanese were flanking around the Australians, trying to find a gap to the north and encircle the defenders. The battle lasted overnight, Colonel Owen still putting his life thoroughly at risk by reenacting the role of Ned Kelly.

Then, at around 3:00 AM, while he was throwing grenades into the jungle with his men, a Japanese bullet shot Owen right through the eye. Despite the best efforts of those on scene, the commander was declared dead shortly thereafter, which put Major Cameron in charge of the Australian force. Shortly after this loss of command and continuing pressure from the 144th, the decision was made to give it up. Australian forces pulled back to positions outside of the town of Deniki.

The (first) battle of Kokoda was over.

Shortly after, however, the unit received a rather nasty letter from a certain someone in general command, who were absolutely livid after hearing of this act of what they perceived as cowardice. Due to the arrival of the rather abrasive and (insert preferred bad word here) United States general Douglas MacArthur and the rather . . . let us say, alleged womanizing, alcoholic incompetent General Blamey, a new policy was enacted in regards to the posturing of high command. This policy essentially broke down into two parts: “shut up and stop whinging, you pack of cowards,” and “she’ll be right mate.”

Going along with this change, the command ordered that a counterattack be initiated as soon as possible to retake Kokoda village. Now, from a strategic sense, yes: Kokoda was important, and the loss of the airfield would be a devastating blow for supplying the forces. However, with their current strength and fighting capability, this was a needless loss of men and equipment that were very much needed to continue the fight further down the track. Nonetheless, while the attack was joined, it was rather uneventful. The three-pronged attack quickly ran out of steam, as skirmishes along two of the paths led them to again pull back to their defensive positions.

The problem was the third prong. They had successfully made it to Kokoda and found no resistance. At first, this seemed good. After all, they did get it back. However, they quickly realized where the Japanese defenders of Kokoda were: heading directly towards Deniki, while the Aussies who had retaken Kokoda now sat miles away from reinforcements and had no way of knowing if they were coming. Due to this, the company pulled together some defenses and waited . . . and waited . . . and waited some more. In all, they waited for three days before saying “screw this” and, after some skirmishes with Japanese reinforcements, made a run for it—straight into the jungle, without even the solace of the trails (due to the Japanese patrolling them), and with no idea where the friendly lines they were hoping to reach were. It is safe to say that they were not having a good time and were rather bitter about this situation.

While A company sat unpleasantly on its heels at Kokoda, further fighting was happening at Deniki. We are going to gloss over this battle here, as we cannot cover everything, because if I submit another article this long, my head will be on a pike. [Ed. Note—Now, that’s unfair. We wouldn’t waste one of our precious pikes on a Shield writer.] Just know that, after a small skirmish, Major Cameron gave the order to pull back to Isurava, ending the battle of Deniki and the Second Battle of Kokoda.

Now, this is where things get interesting. By this point, reinforcements had arrived for both sides. The Australians had received the 58th Militia Battalion, as well as elements of the 2/14th and 2/16th brigades of the REAL army, although these came at different times throughout the battle. Meanwhile, the Japanese had received even more elements of the South Seas Force, including three regiments of the 144th, although they were further up the track at the start of the battle. Further reinforcements included units of engineers and more mountain guns. These forces were to face off at the meeting point of Isurava.

The geography of the area was a quintessential example of the terrain of the region: a large valley covered in jungle and kunai grass. A stream followed the valley, with small townships (the aforementioned Isurava in this case) and buildings down the trails. The Aussies quickly got to work, with their knowledge of the terrain being key to the defense. The general strategy was to hold the hills and make killing zones out of flat non-jungle areas through the use of machine guns and high-volume rifle fire to suppress and pin advancements. These were made in such a way as to interlock different dedicated positions with overlapping fields of fire. These are textbook maneuvers, but that made them no less deadly.

On the 26th of August, the battle of Isurava began with a main line assault around the flanks on the ridges and a pinning force going through the valley. However, the Aussies had prepared well, and were finally in a position where they knew exactly where the enemy were attacking, so now the real stand could begin. The initial Japanese assault was quickly suppressed and took heavy losses charging into machine gun and rifle fire. While the Australians were still taking losses from Japanese snipers and those mountain guns, the Japanese had another major force working against them: time. They realized that they needed to completely destroy this force and eliminate it as a threat if the Japanese wanted to advance across the Owen Stanley mountain range before the Australians could be fortified by reinforcements that were already on their way.

This urgency, however, had disastrous consequences. It forced Horri, commander of the Japanese forces, to order a grueling forced march of all reinforcements to reach Isurava, which also caused supply issues on his side to worsen even further. The Japanese encroached in two main areas, both directly forward along Isurava and the ridges around it, while a second force attempted to cut the Australians off by going along a secondary track where they were engaged around the settlement of Abuari. The 39th was in charge of the main Isurava defense and was holding quite well despite the intense fighting and numerous casualties among their men and also among their defensive emplacements, as their cover was slowly whittled down by mortar and mountain gun fire. The same could not really be said for the 53rd however; they were holding on by the skin of their teeth. These ragtag forces were both under immense pressure, but there was hope as the full battalions from the 14th and 16th were near, and would be there soon if they could hold on for long enough.

By the second day of the battle, things were slipping further, but were not yet completely uncontrolled. By the end of the day, as many accounts specify, areas of the jungle and tall grass had literally been cut down by the intensity of fire, which lessened cover and increased casualties. With this stress on the lines, the Japanese make a fatal mistake.

A flanking attack by the 3/144th, which was supposed to be the killing blow to the Australian force, loses its place, and instead of surrounding the Australian force, attacks its west due to being lost in the jungle. This mistake initially puts even more pressure on the defenders, leading to them losing a few vital positions on the west—and then, a certain someone by the name of Bruce Kingsbury decides he’s had enough.

After hearing of the Japanese advance and getting into the area, he jumps up with a Bren machine gun in hand and starts charging the Japanese force that had pushed them back. With a mate of his, Kingsbury pushed forward, reportedly killing something like ten enemy soldiers in this charge by hip-firing his Bren while moving towards the enemy lines. Seeing this, the rest of the men guarding the retreat were inspired, and jumped up to join him and together managed to wrest back the position from the enemy. All was not good, unfortunately; at the end of this heroic charge, Kingsbury was shot dead by a Japanese sniper. However, his sacrifice led directly to the position holding and helped stall the Japanese advance. Kingsbury would be posthumously awarded the Victoria’s Cross, the most highly coveted medal for combat in the British Empire, and enshrined into Australian legend for the rest of time.

With this legend made and a dire frontline situation, as more and more Japanese forces pour into increasingly difficult positions, we leave for now.

We will pick this up next time. The next article in the series will encompass the full retreat back to Irowaba and the halting of the Japanese advance. Thank you for reading.

Sources:

- Kokoda, by Peter Fitzsimons

- The Kokoda Track (Australian Department of Veterans Affairs)

- Australian War Memorial