Despite the massive scope of World War II, many nations who made important contributions remain overlooked, among which is my home nation of Australia. We fought in this war, not only due to our colonial commitments, but for our very survival. With our so-called British masters hung up in Europe and our links to the USA being slowly strangled by the rapid advance of the Japanese, Australians had to fight for every inch to keep their country open.

At the peak of this, the Australian Army’s supply lines were cut, requiring them to go one-on-one against the Japanese Empire on the Kokoda Track, a struggle of unique proportions where the brave Australian and Papuan men fought tooth and nail in dense jungle across the Owen Stanley Range, going days without food and water in a campaign where disease killed more people than bullets. This was Australia’s Stalingrad, their Battle of Britain with the enemy only kilometers from the largest naval base in the region and, essentially, Australia’s front door. This is the story of the thousands of Australians and Papuans who stood up and defended their homes despite being overwhelmingly outnumbered and outgunned, performing heroic feats all the way through and surviving only by relying on one of Australia’s core principles: mateship. As Winston Churchill might have said, it was their finest hour.

Before we crack into the Track, we must first get a bit of important background information out of the way, although I promise I will be brief.

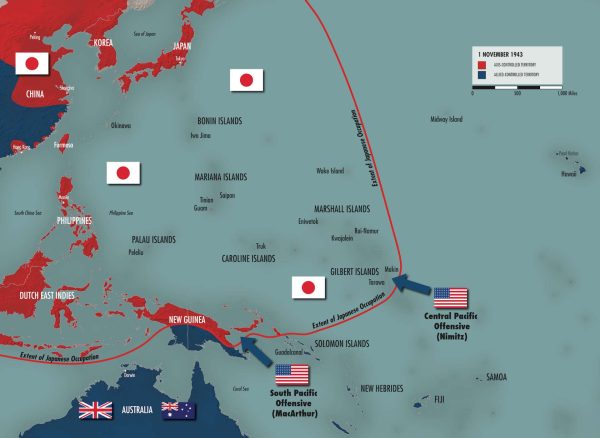

As we all know by now, the Japanese Empire in WW2 was working on establishing its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, which eventually required it attacking Pearl Harbor and declaring war on the United States. One thing often forgotten however was that the Japanese also declared war on the British, its subjects in the region, and the Dutch East Indies, currently known as Indonesia. By mid-1942 they had conquered up to the periphery of Bengal and down into Papua, holding Rabaul and some other northern bases.

As we all know by now, the Japanese Empire in WW2 was working on establishing its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, which eventually required it attacking Pearl Harbor and declaring war on the United States. One thing often forgotten however was that the Japanese also declared war on the British, its subjects in the region, and the Dutch East Indies, currently known as Indonesia. By mid-1942 they had conquered up to the periphery of Bengal and down into Papua, holding Rabaul and some other northern bases.

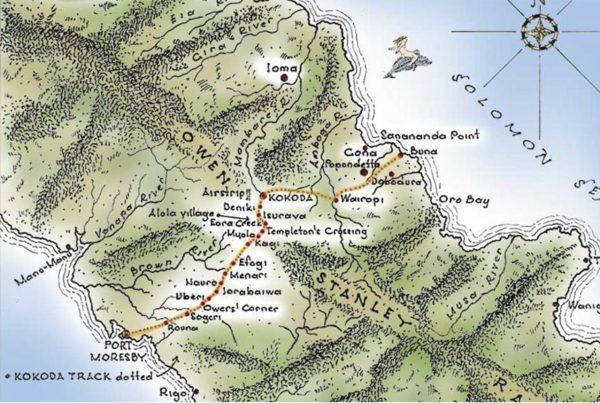

Now I should probably explain why this was a VERY big deal and for that we shall enhance and take a closer look at a map of the South Pacific. Here we see that Australia is close to the area, and people are naturally worried. The area we are talking about is the Huon Peninsula, which has a few major landmarks. The first is the Owen Stanley Range. This was a mountain range with thick jungle, and one of the most secluded places on earth. Its only infrastructure was rough-cut muddy trails, which were really mountainsides with only slightly less vegetation than the rest. This mixing of trails was the track that they were fighting on: mud-caked, mosquito-ridden, jungle-infested, and despite the mountainous terrain, it was to be the area where Australia would fight and define itself. To the south lies Port Moresby. This was the largest port facility in the area, and therefore the best staging point for an invasion of the Australian mainland. The rest of the settlements in the area were tiny locations of breaks in the jungle, mostly featuring some wooden shacks. Lastly, there was another somewhat major town named Kokoda. This was where the track got its namesake and was where the bulk of the early fighting happened. This town was very important, as it had an airfield, which allowed for aerial resupply and removed the need for native carriers.

The Japanese landed at Buna on July 22nd 1942 to start their the campaign. The force on the Japanese side was the South Seas Force, who were an elite unit in the army. They had become veterans fighting through China and the islands in the South Pacific, distinguishing themselves by their record of victory. The main force to go down the track was the 144th Infantry Regiment, a fierce opponent who had specialized jungle training from the elite jungle training schools on Formosa, some of the best equipment in the whole Imperial Japanese Army, and even specialized equipment, such as mountain guns made for just this environment, that we will get to know very well.

The Japanese landed at Buna on July 22nd 1942 to start their the campaign. The force on the Japanese side was the South Seas Force, who were an elite unit in the army. They had become veterans fighting through China and the islands in the South Pacific, distinguishing themselves by their record of victory. The main force to go down the track was the 144th Infantry Regiment, a fierce opponent who had specialized jungle training from the elite jungle training schools on Formosa, some of the best equipment in the whole Imperial Japanese Army, and even specialized equipment, such as mountain guns made for just this environment, that we will get to know very well.

On the Australian side, at this time, there was the 39th Brigade and the Papuan Infantry Battalion, or PIB. The 39th was a militia brigade that had only been called up about two months before this, was made up of many people rejected from the army who mostly had no prior experience, and was equipped with only the finest and most advanced weaponry of the First World War, including old Vickers and even Lewis guns. The PIB was not much better off. They were a group with barely any guns, no training, and were not that keen to fight. At the time of the attack, there were about 400 men on the Australian side against the roughly 800 Japanese, but the Australians desperately needed to hold, as it would only get worse if they lost the Kokoda airfield.

The Japanese advanced on bikes, but little did they know they were about to get a surprise.

“Wait” whispered Chalk, a commanding officer of the PIB, as he and his mates saw the mass of Japanese on a bicycle pass.

“Hold,” he whispered again; he said “Wait.”

Then, all of a sudden, shots rang out from a machine gun, landing right into the Japanese formation and knocking many off their bikes. A second later, a scream of “NOW” caused the jungle to erupt with rifle fire, as submachine guns, grenades, and machine guns also opened up from the brush. Man after man fell from the formation as the Japanese scrambled to reach their weapons. They were well trained, though; they kept up fire to suppress the Australians as they maneuvered around the flanks, firing mortars for fire support. Before long, the Australians began running to avoid encirclement as the return fire intensified. With big grins on their faces, they pulled back from Gorari knowing they had done it: caused the first Japanese casualties of the campaign. The morale was still quite high as they pulled back to frantically tell their mates. This ambush was quite the success, as it caused numerous casualties while the Australians lost only single digits in wounded and dead.

The men pulled back and went to set up the next ambush, but now that the Japanese were on guard, the battles to come would not be as easy. The IJA were only beginning here, and would unload many weapons used to deadly effect through the campaign. These included mountain guns (artillery that can be dismantled and carried in pieces) and more mortars to support them, as well as the camouflage netting to hide them, and even support equipment like treatments to the many diseases in the area, such as malaria, to further increase their edge.

Here we will leave off for now: the men of the 39th have gained their first blood and infuriated an enemy that they will have to fight with every available resource to protect their base at Kokoda. In the next article, in honor of Indigenous Peoples’ Day, we will discuss the contributions of the native Papuans to this campaign, before we continue with the chronological record.

Bibliography

- Kokoda by Peter Fizsimons

- Australian War Memorial – https://www.awm.gov.au/papua-campaign/kokoda

- Japanese conquest picture – National WWII Museum – https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/pacific-strategy-1941-1944

- Kokoda track picture – Kokoda walkway – https://www.kokodawalkway.com.au/education-centre/educational-resources/

- 39th lined up photo – Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kokoda_Track_campaign