Everyone knows about the classic fairy tales: Cinderella, the Little Mermaid, and pretty much all the other ones Disney movies monopolized. You know, the ones children (and parents) all across the world know and love.

But have you ever considered where these stories came from?

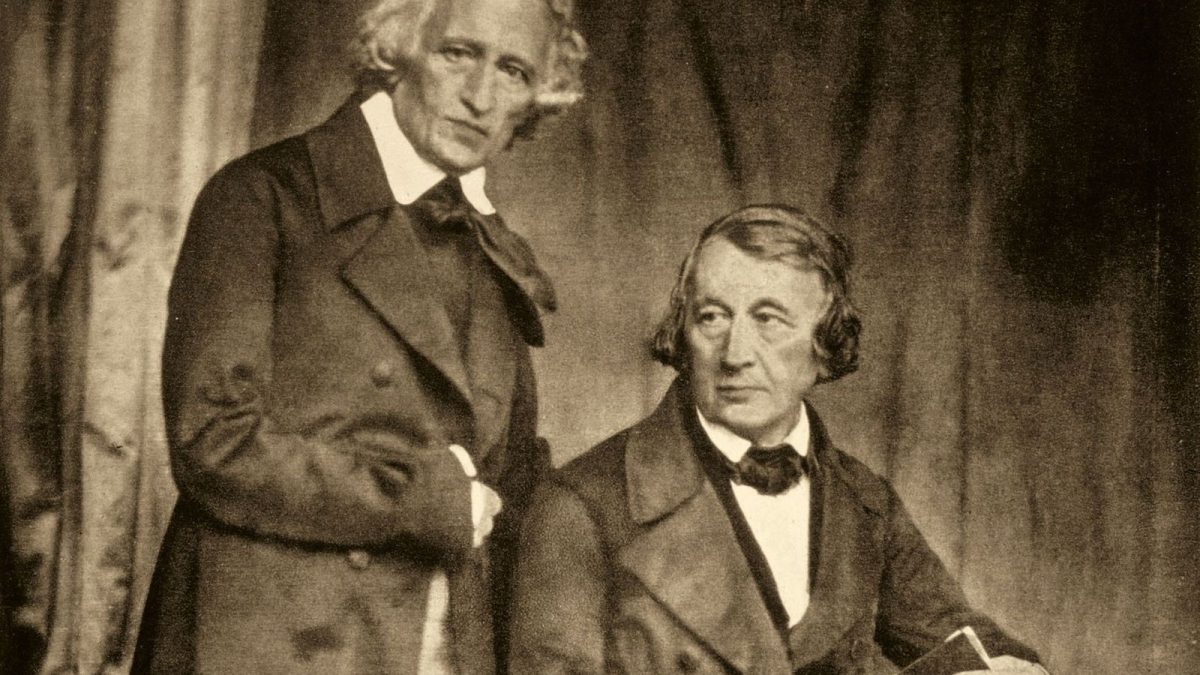

Many of these tales originate from Europe, and were published for the first time by the Brothers Grimm. The revival of folklore and legends were a product of the Romantic movement of 19th-century Europe. The Brothers Grimm spent a majority of their lives dedicated to uncovering and publishing these various stories that were passed down by generations, which is why us modern people still know them. It was later that people started cutting the cruel parts out.

Hopefully, you DO know these stories were not actually intended for children to digest, but rather originated as old folklore and legends.

Yet in Germany, they didn’t care to filter the contents. A German childhood involves trauma, after all. [Ed. Note—We’d argue dang near every childhood in the 19th century involved trauma.] These stories are a bit more disturbing than the pleasant ones we are so used to here in the States. They tend to focus more on being blunt with their lessons than sugarcoating it.

While there are just simple changes to the tales we already know (like one of Cinderella’s sisters cutting her foot to fit the size of the slipper), the most interesting ones must be those that are specifically found in German households.

Those were written by Heinrich Hoffman, a psychiatrist who could not stand undisciplined and naughty little children. He wrote a series of stories called Der Struwwelpeter (literally “shock-headed Peter”) featuring stanzas and illustrations to fit them. He originally wrote it to give as a Christmas present to his three-year-old son (thanks Dad!), but other people loved it so much they just had to publish it.

So here are some of my favorite ways to ruin your children’s innocence for the sake of good behavior, using the wondrous stories and cultural treasure that are Heinrich Hoffmann’s German fairy tales.

N.B. Before we begin, we must make one thing clear: neither the authors of this article, nor Mr. Morales-Bermúdez, nor the Morales, nor any other members of the Shield staff take any responsibility for any tears or shrieks caused by your endeavors in German fairy tales. Be warned.

Story 1: Zappelphilipp

Our first story from Der Struwwelpeter is called “Zappelphilipp,” aimed at stopping noisy and fidgety children at the dinner table. This story is more light-hearted and rather humorous compared to other ones in the book.

This is how the story goes:

There was a kid known as Fidgety Phillip. He always misbehaves at the dinner table.

“Young man, please stay still at the table!” says the father.

“No! I will not stop fidgeting!” replied Phillip.

So Phillip kept shaking and moving around, then his father scolds him again.

“Stop misbehaving and just eat your dinner!” his father yelled.

Once again, Phillip ignored him. Then he fidgets his way off his chair. Phillip falls, the tablecloth and plates going with him.

Obviously, this is not that bad. Phillip simply fidgets around too much and falls off his chair. This is very tame compared to the other stories found in the collection.

Story 2: The Very Sad Story with the Matches

This story is supposed to teach children to be obedient to their parents or else they will hurt themselves. Hoffman could have used literally any other example, but chose the one about matches. (His sanity might be low.)

The story goes as follows:

Paulinchen was home alone, because her parents were out. She was playing around the house until she saw a matchbox. She sees it and says, “That must be a wonderful toy. I’ll light the match just like mother has often done.”

And Minz and Muanz, the cats, warned her: “Daddy forbade it! Meow meow meow! Leave it alone! Otherwise you’ll burn to death!”

Paulinchen cannot hear the cats’ warning, so she lights the match. The match flickers and crackles, and Paulinchen is having a lot of fun. She skips around the room, but the cats warn her again: “Mommy forbade it! Meow meow meow! Otherwise you’ll burn to death!”

But she cannot hear them! The flame reaches her dress, setting it on fire. Her hand, her hair, the entire child is burning.

The cats then cry in desperation: “Hey! Who will help us? Meow meow meow! Help! The child is burning!”

Everything is completely burnt, the poor child with skin and hair; only a pile of ashes remain, and two shoes so soft and delicate.

Then Minz and Maunz sat there and cried: “Meow meow meow! Where are the poor parents? Where?”

Their tears flow like a stream through the meadows.

Hoffman goes from Fidgety Phillip to being burnt alive. I wonder what personal experience he had to create this one. Remember, share this story with kids if you want them to stay away from matches.

Also: The Brothers Grimm

I hope you had fun with our contributions from Der Struwwelpeter, but I must talk about the Brothers Grimm as well.

In their version of Snow White, the stepmother is far more terrible than the monopolized version. She hires “The Huntsman” to actively kill Snow White; she also has plans to eat her flesh.

This is a story the film monopoly stays completely clear from: How Some Children Played at Slaughtering. This very fun little story is exactly what you expect: a butcher’s family ends up being torn apart because one of his sons decides to play at his dad’s job. One version is more thoughtful, since the boy is tried in court, but because he is so young, the court doesn’t know how to handle the case. The other, less interesting and more disturbing, ends in the entirety of the family dying. I have no idea what it’s trying to say. Maybe don’t play around with knives?

Honestly, these stories have been both fun and gruesome. However, be aware that there are far worse ones than those I have shown to you. I, for your safety (and mine as well) [Ed. Note—and that their publisher wouldn’t allow it], will not share these to you.

Remember, these tales were not originally intended for children, but rather oral traditions the Brothers Grimm recorded. When their compilations of stories got around to mothers, they had to cut bits and full stories out of the copy, saving future generations from witnessing the actual horrors.

As for Hoffmann . . . I wonder what devilish 3-year-old he had to deal with that prompted him to write his book.